Research Part II

"Victorian rich people gifts" and other Google searches, plus my secret weapon

Last week I covered how I approach the bulk of my research, the preliminary research before I start writing. This week I’ll be covering archives and *whispers* the internet.

Of course I use the internet for general research, but I don’t like to rely on it. I prefer to know exactly where a source has come from, and vast reams of the net aren’t as, well, legitimate as published non-fiction. If I must look something up online because I’ve just realised I need it, which of course happens about twenty times a day, I try and tie it to a reputable source, for example JSTOR, a digital archive of journals, books, published scholarly articles and images. For The Household, I also found Victorianlondon.org very useful, as it clearly states sources for all its content, and is organised like an encyclopaedia.

The internet is a means to an end for on-the-go research, when you have a burning question that you need an answer for right now. It’s impossible to be able to account for everything in preliminary research; of course I don’t know in advance every single sentence I’m going to write and every image contained within it.

An example: in The Household, Angela receives a gift from her stalker. But what sort of gift would befit a woman of her status? What was the upper-class Victorian equivalent of Bloom & Wild? I was in flow writing when this came up, and I find instances like this jarring because I’m not someone who can write “XXX GIFT HERE” and carry on. I have to know it there and then and put it into the story. And so I googled “Victorian rich people gifts”.

This is where common sense often triumphs over accuracy. The first result is “Ten ways to celebrate Christmas like a Victorian” which is not exactly what I was looking for. The article reads: Gift giving was traditionally part of New Year celebrations, but the Victorians used Christmas as an occasion for giving fruit, nuts, sweets and small handmade trinkets to their loved ones. Handmade games, dolls, books and clockwork toys were popular, as were apples, oranges and nuts.

The scene doesn’t take place at Christmas, and anyway, nuts didn’t seem right somehow. I then had the idea of a Fabergé egg, which is suitably gaudy and overblown, but a quick search informed me the first one was made in 1885. Fine. Back to the internet. A few down from the top search is a blog referencing more Christmas gifts in the late 19th century, which is 50 years after the time my book is set, but the author uses magazine editorials and advertisements as sources, and soap is one of the gifts she references. Scented soap is exactly the sort of thing that would fit. It’s feminine and intimate, and because it’s sent by Angela’s stalker, suitably creepy. In this case, I didn’t mind using a source from 50 years in the future because another quick search informs me that scented soap was indeed used in the 1840s. I always like to check the origins of any item or “prop” I’m using, but sometimes anachronisms slip through and are picked up later.

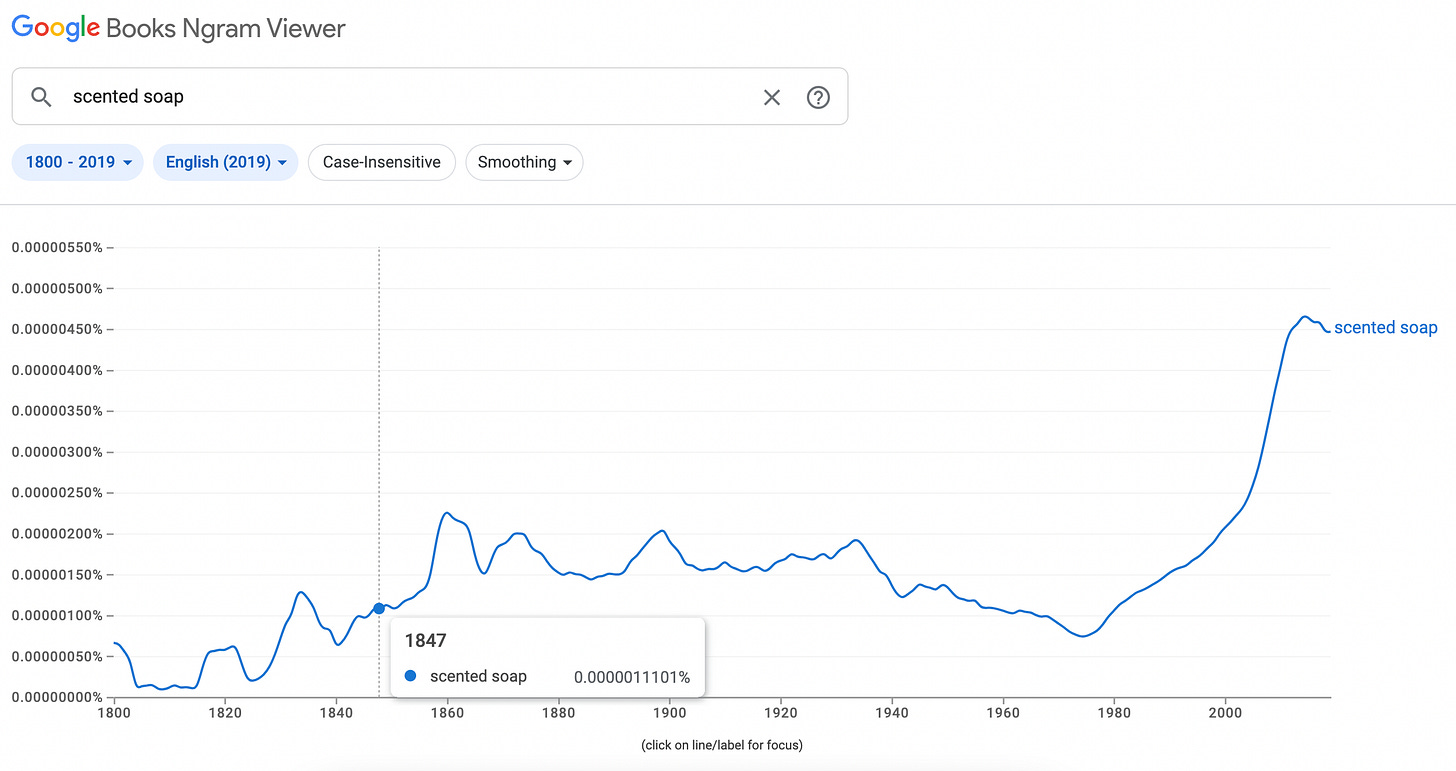

The best way of ensuring something was in circulation at the time I am writing is Google Ngram. Frankly, it’s genius. Ngram is a piece of software that allows you to search a word or phrase in books and journals published from the beginning of the 19th century. The search for “scented soap” looks like this:

The graph shows the prevalence of the word in Google Books’ samples of books published in the English language dating from 1800. Though the words “scented soap” were present in 0.0000011101% of Google Books’ sample from 1847, they were present, which means the term was in parlance. That’s all I’m looking for. You can then click the tabs at the bottom to see the term in published titles; the first two results pre-1850 are A Dictionary of Arts, Manufactures, and Mines (pubd 1843) and The Farmer's Dictionary (pub 1846). This is good enough evidence for me to go ahead with the term “scented soap”. If the line is flat at 0.00000000% and doesn’t rise until after the period you are writing in, it means the word or phrase was not in published works at that time, therefore possibly not in use. I use this tool all the time while writing, and I mean literally every few sentences. It doesn’t work for everything, for example slang, because the people using slang were generally not the people writing books in 1847. But it’s a very useful tool, and sort of my secret weapon.

Archives

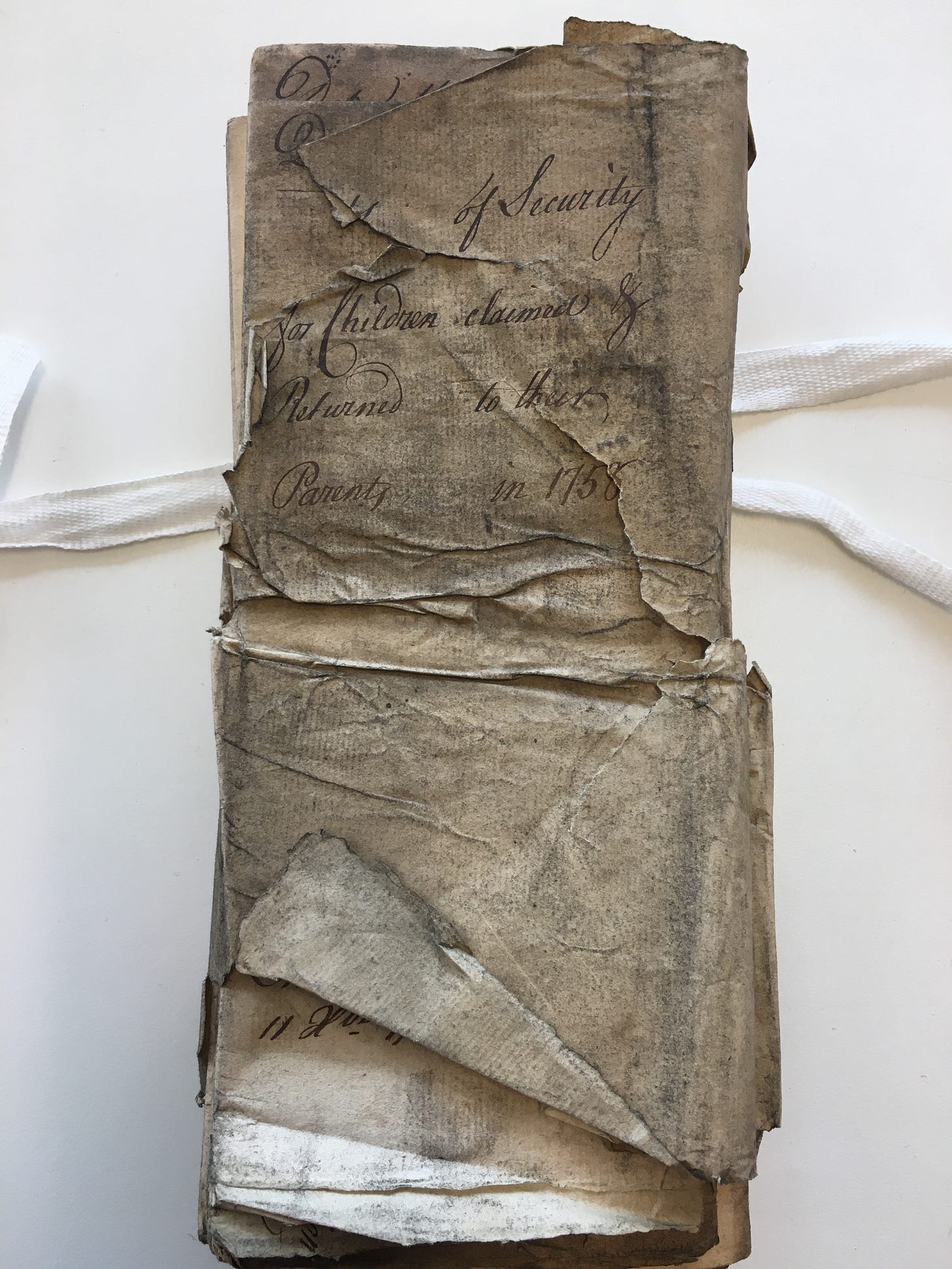

I know that archives are the bread and butter of a historical novelist’s research but *whispers* I don’t really use them. I have in the past but find their systems impenetrable and daunting. I know archivists will be disappointed by this, and I will say the few I’ve encountered, mostly on email, have been very helpful. When I was researching The Foundling, I naively just turned up at the London Metropolitan Archives and asked if I could see some of the tokens left with the babies at the Foundling Hospital. The assistant there explained I’d need the exact reference number for each item, which of course I didn’t have. I sat at one of their computers for a while, trying to make sense of the catalogue, but I didn’t have anything specific in mind. Though I did manage to find reference numbers for receipts taken when people collected their babies in the mid 1700s, and felt a private thrill unboxing the 350-year-old deeds, untying the frail ribbon that bound them, wondering when the last time was that they’d been handled. The first in the pile was a heartbreaking record of a mother who returned for her baby boy, who was “violently take from her” by her husband and brought to the hospital. She appeared the next day to reclaim him, and no charge was payable.

Sometimes you need to know something very specific, and no matter how much detective work you do, the answer remains elusive. This also tends to come up while writing rather than in preliminary research. I’ve contacted archivists via email before with specific questions when my own digging has produced nothing or conflicting information. Local archives tend to be the best route towards an answer. Examples of times I’ve needed to do this included wanting to know if family would be able to attend the funeral of a patient who died at Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum. For this I contacted Berkshire Record Office. For The Household, Wandsworth Libraries & Heritage Service were able to tell me exactly where Wandsworth police station was located in the late 1840s.

Most maps are available online, and are a hugely significant aid in research. I like to bookmark them and have the tab open while writing scenes so that I can follow and direct the characters. Photographs, too, are wonderful, if you are writing in a period in which they existed. For Mrs England I had a folder of about 100 from Calderdale Archives, of Hardcastle Crags and the landscape surrounding it, and Edwardians in their Sunday best bathing in the river.

Sources

A quick note on sources. If you’re writing fiction, you will probably prefer to use secondary resources. This refers to material that is not original. If you are going to an archive to look at letters, or gathering information yourself through censuses, newspapers etc, those are primary resources. If you are buying books or reading papers by people who have gathered the research and are distilling it back to you, that’s secondary research. With secondary research, you read it through a lens, usually that of the scholar or historian who has compiled it. Dickens’ letters, for example, are primary sources. Claire Tomalin’s book is a secondary source.

Depending on the work you are doing, primary is not necessarily better than secondary and vice versa, as long as you are aware of the distinction and the limitations that apply if you are relying on secondary – and the sheer work involved when digging through the former. This gets a little cloudy when you are using published or curated collections of a primary source. For example, the Shuttleworth household receipts I used at the British Library were not the actual 17th century originals: they had been collated and published in the Victorian era. It doesn’t matter, necessarily, but I can’t be 100% sure that every single item made it into that book. Sometimes I wish I was the kind of writer who could spend two years in archives doing my own research, then another two writing the novel. But I don’t have the time or attention span to spend so long at one thing.

Obviously your story will direct your research. If you are writing a novel based around the Regent’s Park ice-skating disaster of 1867 and you want it to be as true to actual events as possible, the first place to start would be seeking out newspaper cuttings about it. For the general setting, books on the Victorian era and Victorian London would probably suffice.

Hopefully this has made anybody wondering how to start researching or writing a historical novel feel less intimidated. You don’t need PHD level knowledge of a period or topic to write about it. I didn’t study history past GCSE level. I’m not an academic or an authority on any area, in fact the world of theses and PHDs and university libraries is very alien to me. I just love researching things I’m interested in.

Finally, probably the most important part of research is knowing when to stop. There is a fine line between learning and procrastination. It’s all too easy to get carried away writing reams and reams of notes and behaving as though you are writing a doctorate. Avoid doing this, and when you feel you have enough to begin, begin, even if you don’t feel you’ve done enough to sustain you through the whole novel. “But you can never do enough research!” I hear you cry. Actually, you can. You can do way too much. When you find yourself scribbling a page of notes on the royal family in the Georgian era, unless you are writing a novel about the royal family in the Georgian era, put down the pen and begin writing your story. Start writing it before you are ready. Information is not knowledge, it’s information. The knowledge will come out on the page.

I’ll leave it there for now. In summary: the internet is fine, but books are better. A life lesson if ever there was one. There will be someone, somewhere, who is able to answer the more specific questions. And last but not least, know when to stop.

My most-used online resources

The British Library catalogue - an amazing way to research, but limiting unless you live near the two locations

Old Maps Online - exactly what it says on the tin. You can also layer modern and historic maps for accurate topography

JSTOR - digital archive of journals, books and images. Registering will give you access to 100 articles per month. Use the search facility to sift through topics of interest

Wob - for second-hand/out of print books that might be tricky to get hold of

Next week: writing about real people